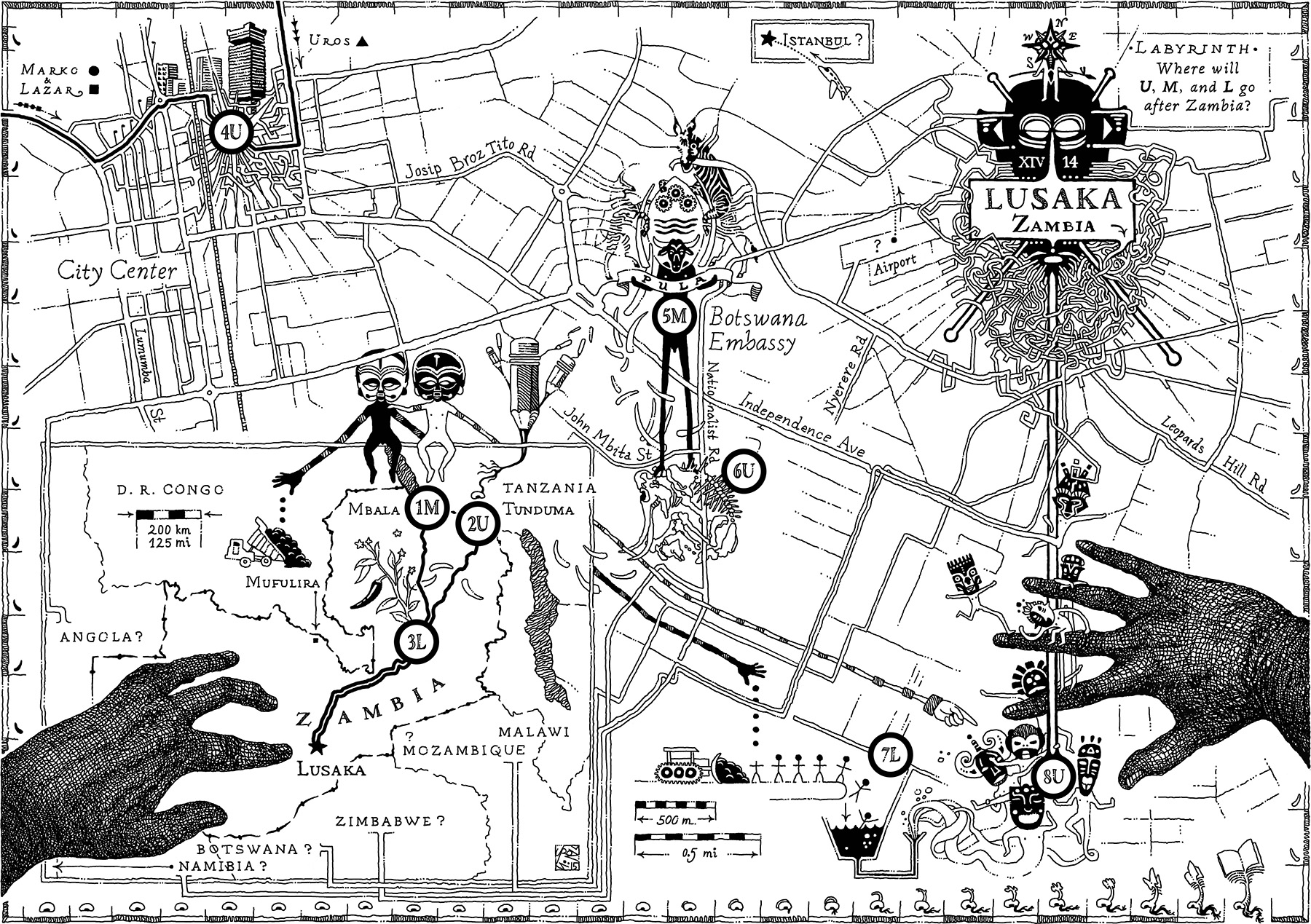

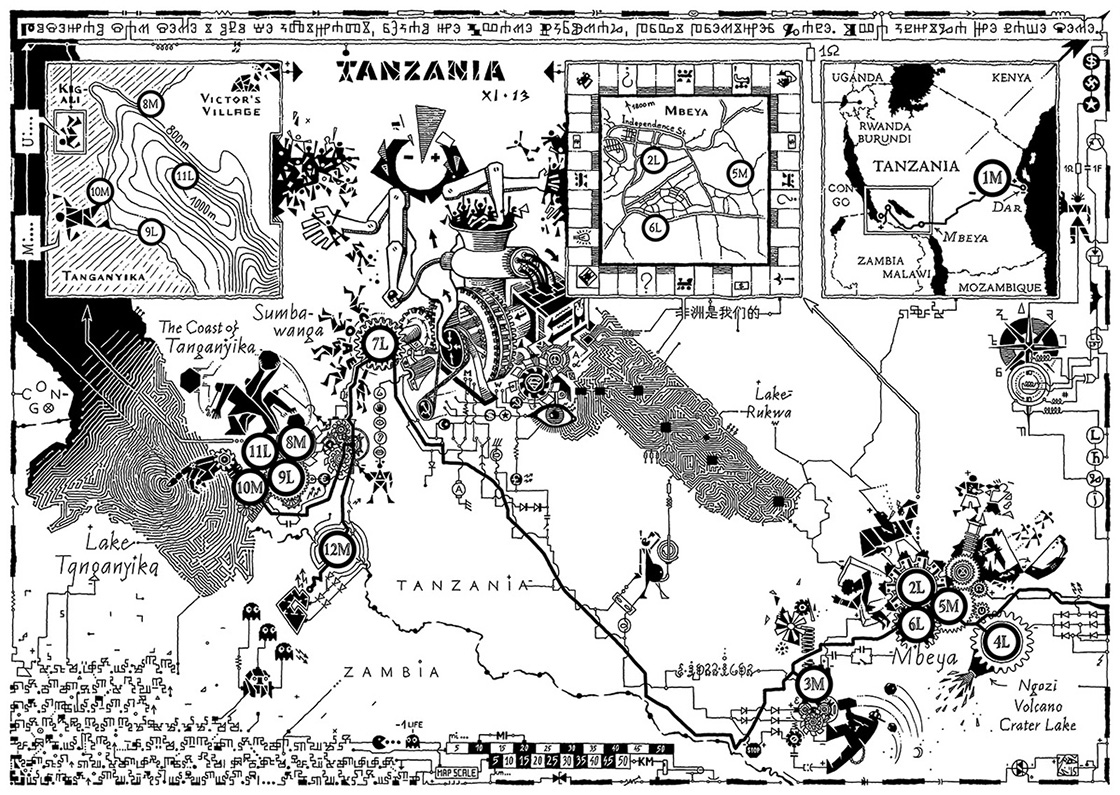

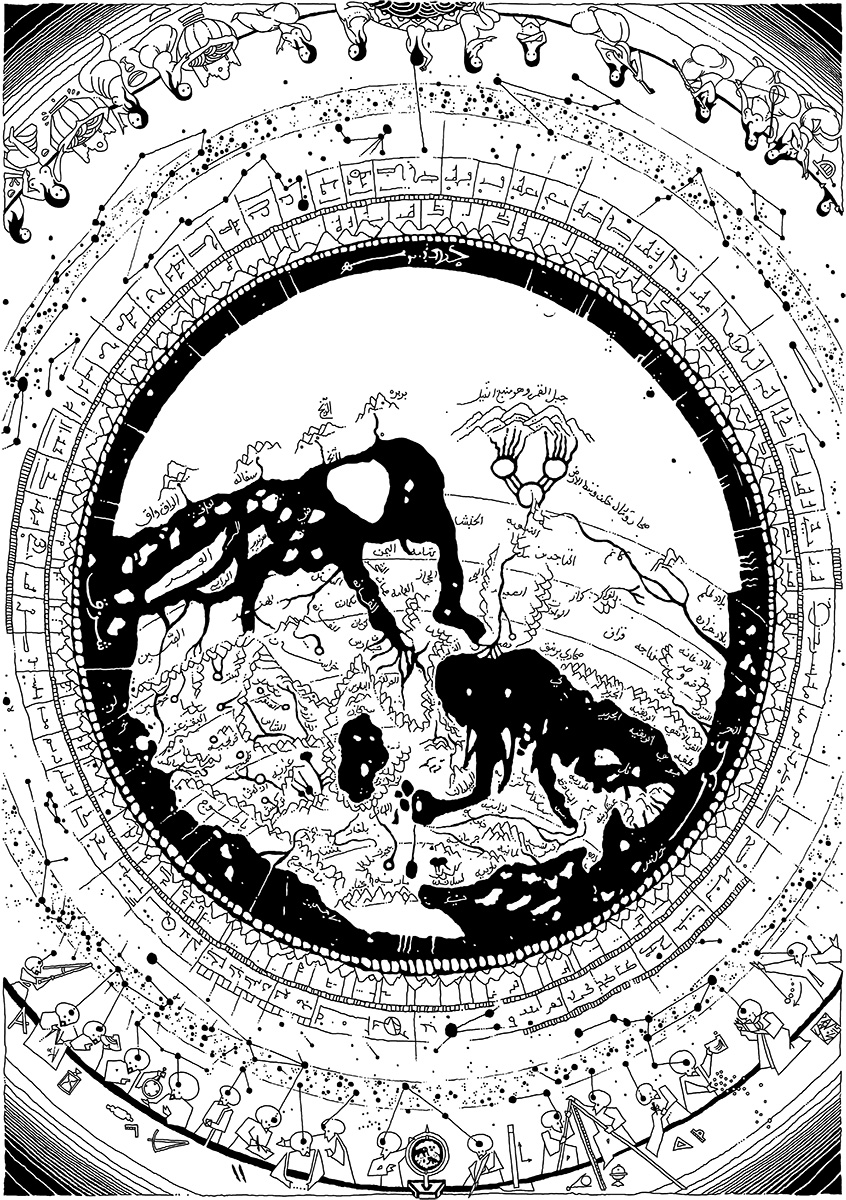

Bantustan: Atlas of an African Journey (Bantustan: Atlas jednog putovanja) is an illustrated travelogue, novel, atlas and encyclopedia. It was written and created by Lazar Pašćanović, Marko Đedović, and me.1 It is at once a textbook for independent travel in Africa, an illustrated atlas, a collection of life stories, an intimate confession, a list of little secrets and shame. Alternating between three narrators, it is a story of division, isolation, contact, and imagining new cartographies of human relationships on a shared globe.

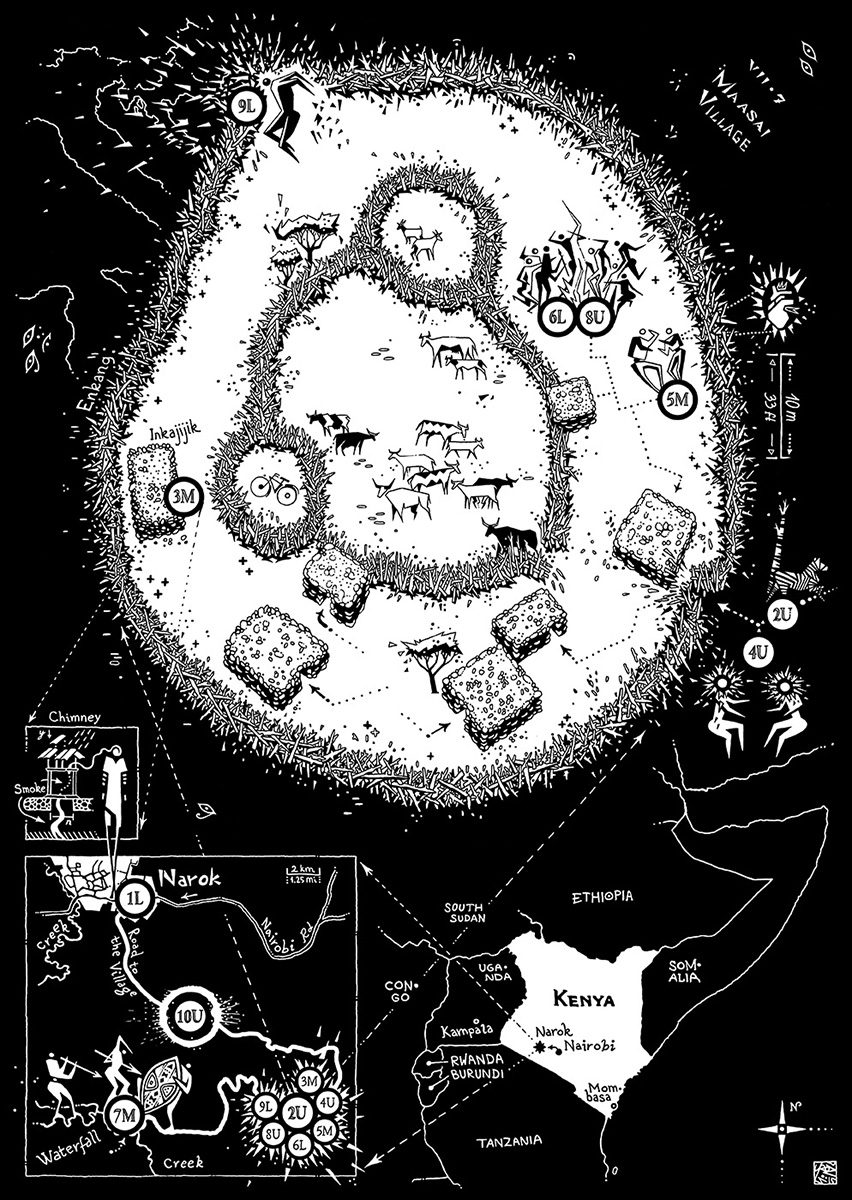

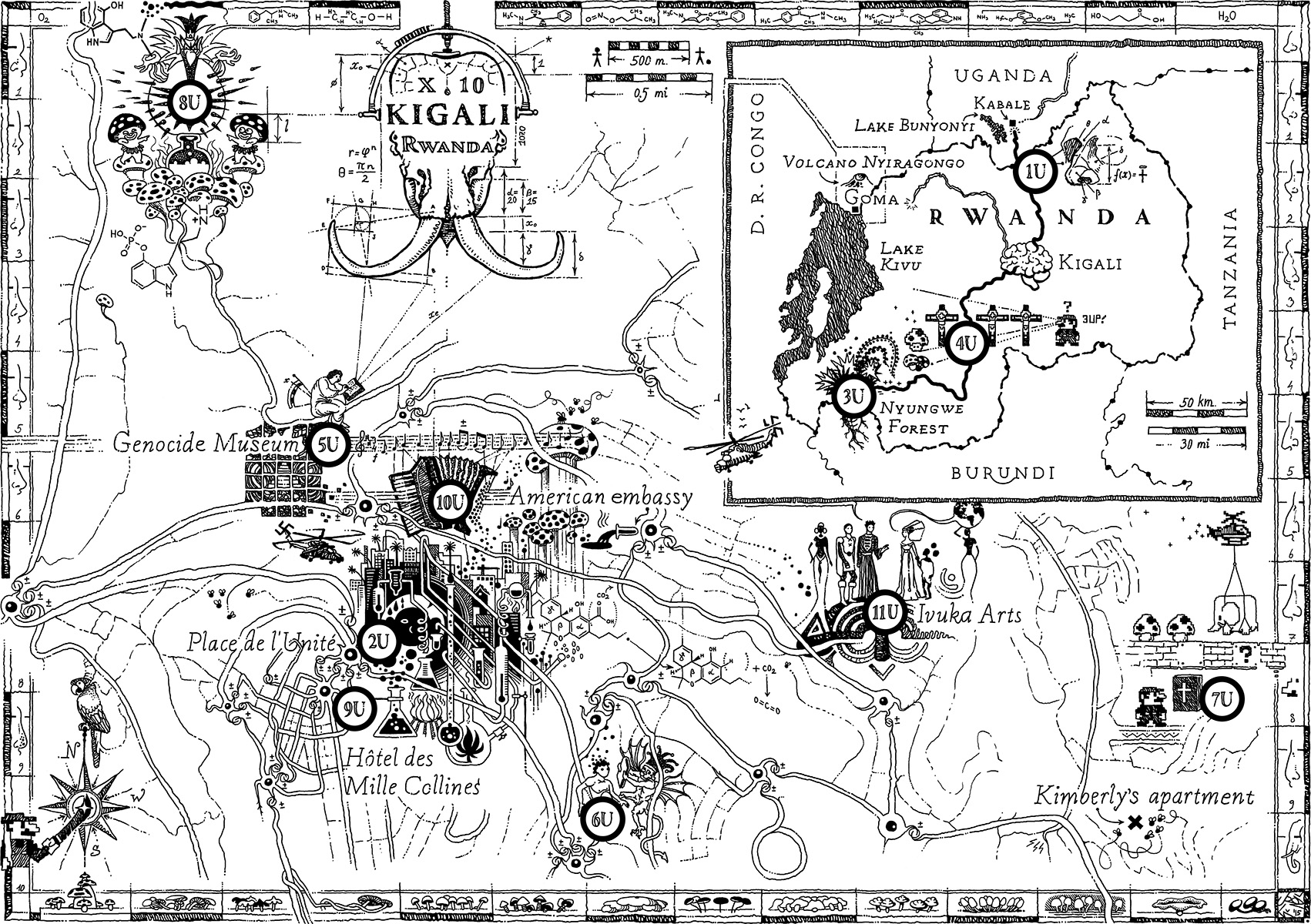

The story follows our 3-month travel across Serbia, Bulgaria, Turkey, Syria, Jordan, Egypt, Sudan, Kenya, Uganda, Rwanda, D. R. Congo, Tanzania, Zambia, and Namibia. The travel project itself, organized in 2010, could be interpreted in the context of psychogeography and experimental geography.2 Using hitch-hiking and digital hospitality platforms, we have tried to meet as a diverse pool of people as possible. Many of them we found thanks to the communitarian philosophy of early CouchSurfing. The question of physical experience of the connected world mediated via digital platforms plays an important role in the narrative.

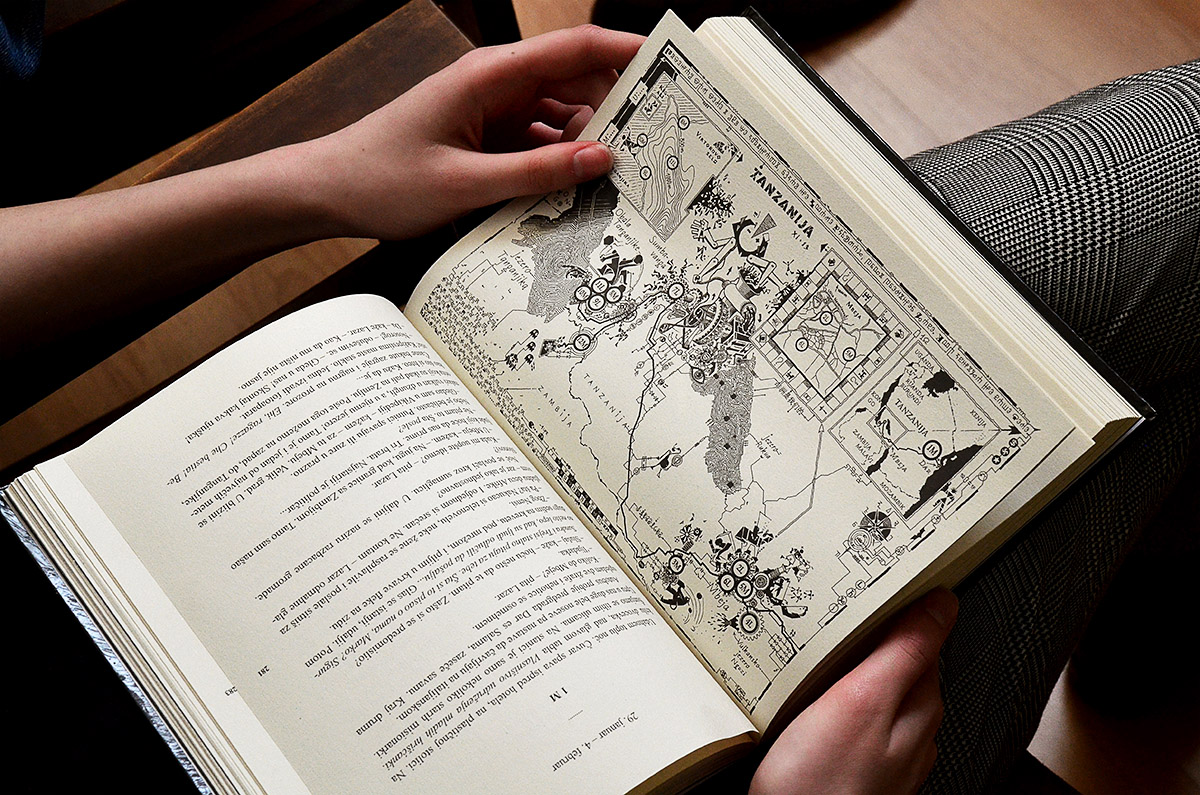

Written in 3 alternating voices, Bantustan is an example of a collaborative writing project.3 Pašćanović, Đedović, and me have collaborated on the final text for several years, turning a travel blog into a cross-genre experimental prose. The English translation of the book was finished by Pašćanović in 2021.

Including a series of hand-illustrated maps, infographics, literary interfaces, and data visualizations for non-linear reading, Bantustan is an example of ergodic and interactive literature.4 Readers can choose how to read the book: in a traditional linear fashion or using maps as visual interfaces for jumping from one story to another.

I've drawn all maps and visuals by hand, digitally, using a drawing tablet. Maps represent a tapestry of pictograms, ideograms, different writing systems, coats of arms, labyrinths, secret messages, and other hidden symbols for readers to discover and decypher. The drawing process lasted a year.

Bantustan contains a total of 32 full-page illustrations, 19 of which are maps, as well as 25 smaller illustrations, visuals, and glyphs.

Bantustans5 were reservations for Black Africans set up by the apartheid regime. They also have an important post-Yugoslav connotation.6 The book draws many connections between the Balkan and African histories and contemporary situations.

Apart from these wider political meanings, however, we refer to bantustans primarily as to the bubbles in which we all live our lives. The three of us, both as authors and protagonists, as well as the people we encounter along the way, are constantly struggling to escape these multi-layered bubbles – of ego, family, social circle, class, race, religion, ethnicity, language, nationality etc – and establish contact with the rest of the world. Such attempts are often painful and sometimes downright disastrous, leading to a series of conflicts, disappointments and crises, but ultimately confirming the possibilities and importance of human connections.

The original Serbocroatian edition of Bantustan was published in 2015,7 as a community non-profit self-publishing project, via a crowdfunding campaign organized by The Travel Club (Klub putnika). This book is currently available as a openly licenced free electronic book.

The hard-cover was printed in 3 editions (3000 copies) and promoted via 30+ self-organized events in Belgrade, Zagreb, Sarajevo, Novi Sad, Rijeka, Banjaluka, Kragujevac, Pula, Mostar, Sombor, Sinj, Konjic, Trebinje, Pirot, Varaždin, Subotica, Čačak, Čakovec, Osijek, Istočno Sarajevo, Babušnica, Opatija, Vršac, Makarska, Pančevo, and other towns in Serbia, Croatia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Vasa Pavković, Serbian writer and literary critic, said the Bantustan “reads like a picaresque novel, but it is also an exciting and authentic testimony about the contemporary world.”

Ildiko Erdei, professor of anthropology at the University of Belgrade, called it “a project of unintentional ethnography and experimental anthropology.”

Elis Bektaš, Bosnian writer and poet, wrote an essay about the book, calling it “a top-notch literature.” He added that Bantustan is “not only a travelogue but also a new form of novel.” ■