In 2008 my lab partners and I started an open project in affective computing, a field that connects computer systems with human emotions. The project was called Synesketch.1 It was a free open-source software library for textual emotion recognition and generative visualization.2 Inspired by the concept of synesthesia, Synesketch was in fact an artificial synesthete,3 software that maps text to generative visuals via feelings. The project started in the pre-post-truth, pre-crisis era, when affective AI technologies were perceived as relatively innocent, especially among programming and creative coding communities.

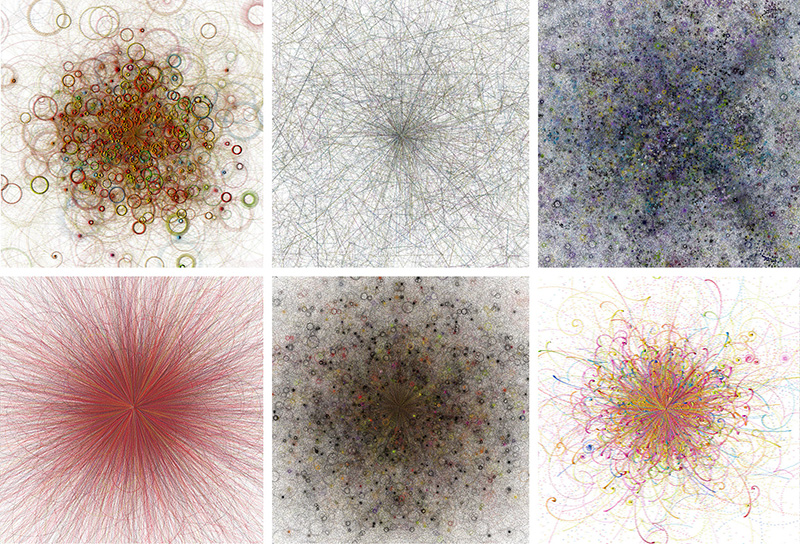

How does Synesketch work? You could, for instance, type in “I am happy” and get a visual swirl of brightly colored particles; or type in “I am not happy” or “I feel heartsick” and get a bluish ocean of twinkling dots.4 Its recognition technique is grounded on a refined keyword spotting method which employs a set of heuristic rules, a WordNet-based word lexicon, and a lexicon of emoticons and common abbreviations.

Twelve years later, however, when I look at the project, I see it as an abstract portrait of data naïveté. It is hard to deny that affective tech has become another tool for digital control, propaganda, affect management, and the exploitation of emotional labor.

For example, in his “Radical Technologies”5 Adam Greenfield writes about Japan’s Keikyu Corporation, which measures the quality of its frontline employees’ smiles.6 Keikyu’s software scans the workers’ eye movements, lip curves and wrinkles, and rates them on a 0-100 scale. “For those with low scores,” Greenfield quotes a Foreign Policy article about the system, “advice like ‘You still look too serious,’ or ‘Lift up your mouth corners,’ will be displayed on the screen. Workers will print out and carry around an image of their best smile in an attempt to remember it.”

Although it has nothing to do with these exact algorithms, Synesketch exists within the same category of affect quantification technologies. What was treated as a digital art experiment effectively became a political-economic weapon. In other words, Synesketch was not only an artsy gadget, it was a small battleship – both an æsthetic object and a tactical object. That is why, a decade later, I decided to reapproach it as such.

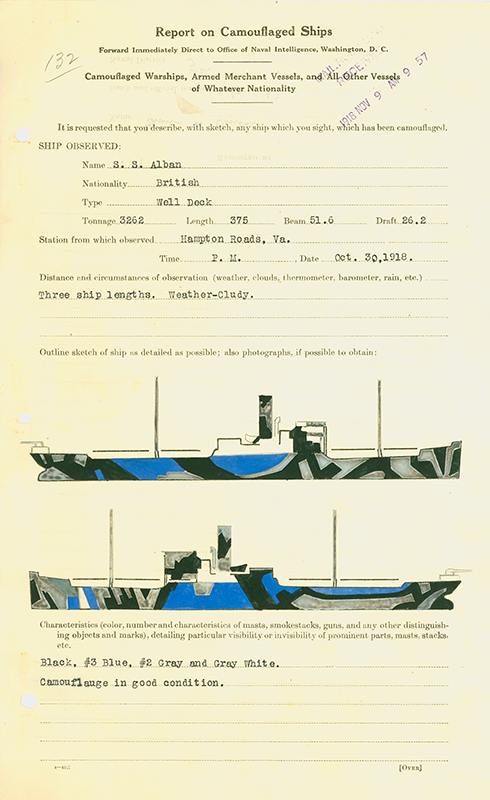

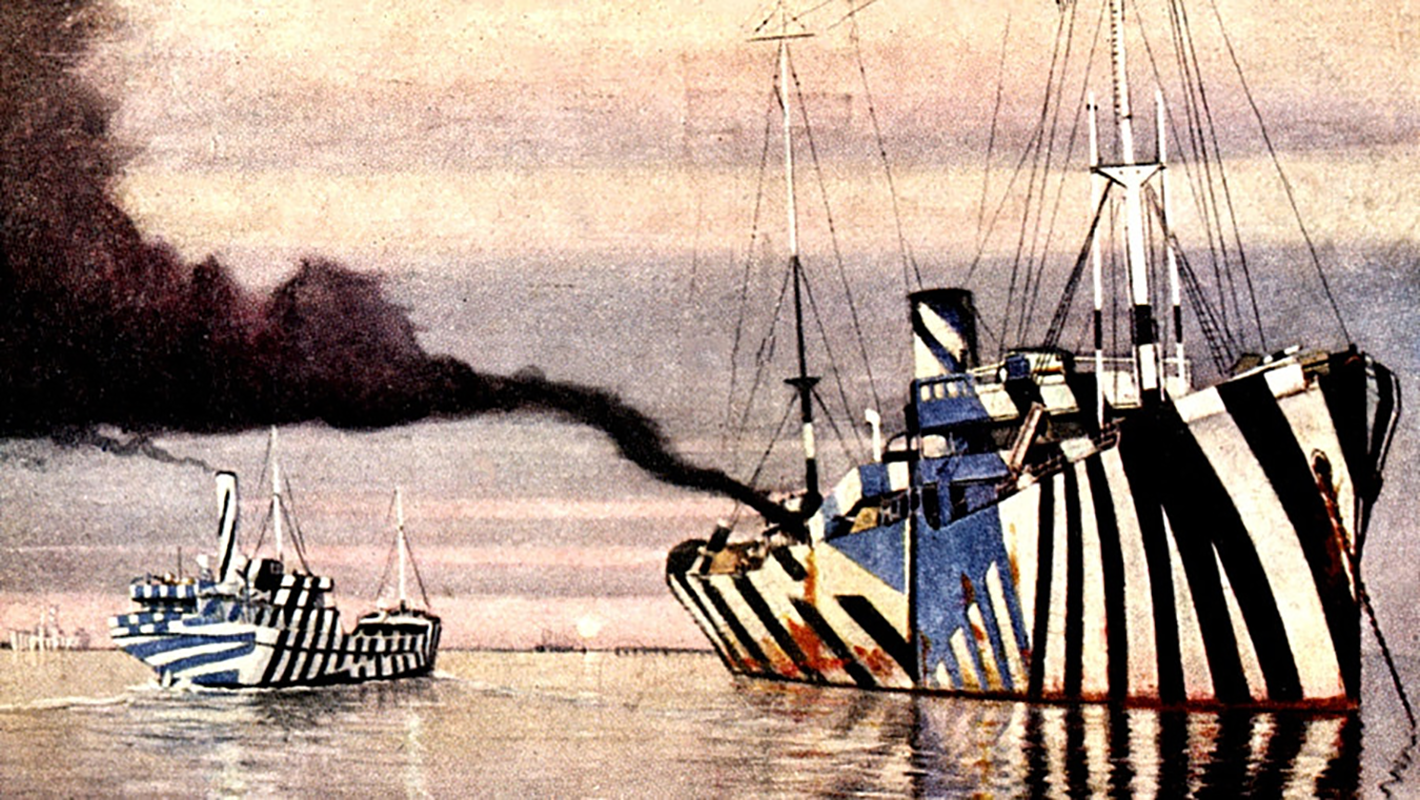

There is an intriguing example from technological history, that combines visual æsthetics and military tactics. Before the First World War, the British and US military started to paint its ships in strange – and rather beautiful – black-and-white zebra-like shapes, in order to confuse German torpedo-equipped U-Boats. This naval camouflage tactics was called Dazzle.7

“This camouflage was not about invisibility”, said the writer and producer Roman Mars.8 “It was about disruption. Confusion.” Artists such as Picasso considered these ships æsthetic objects, even claiming such artistic camouflage was invented by cubists.

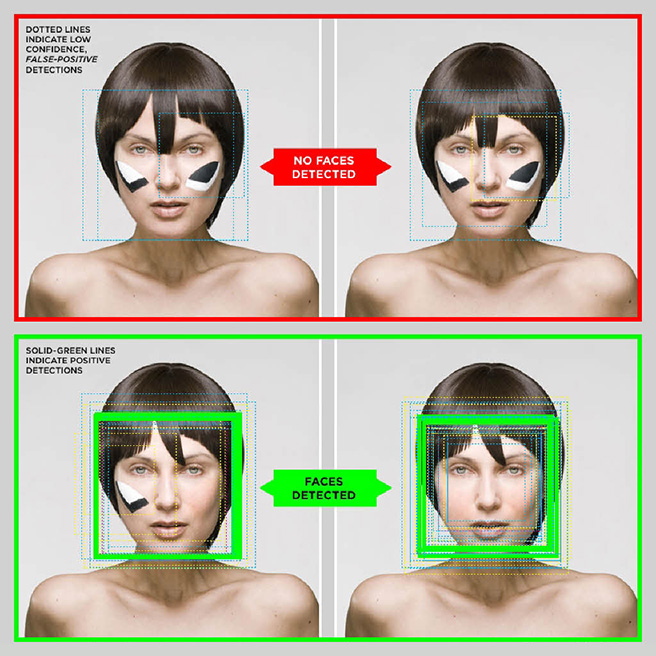

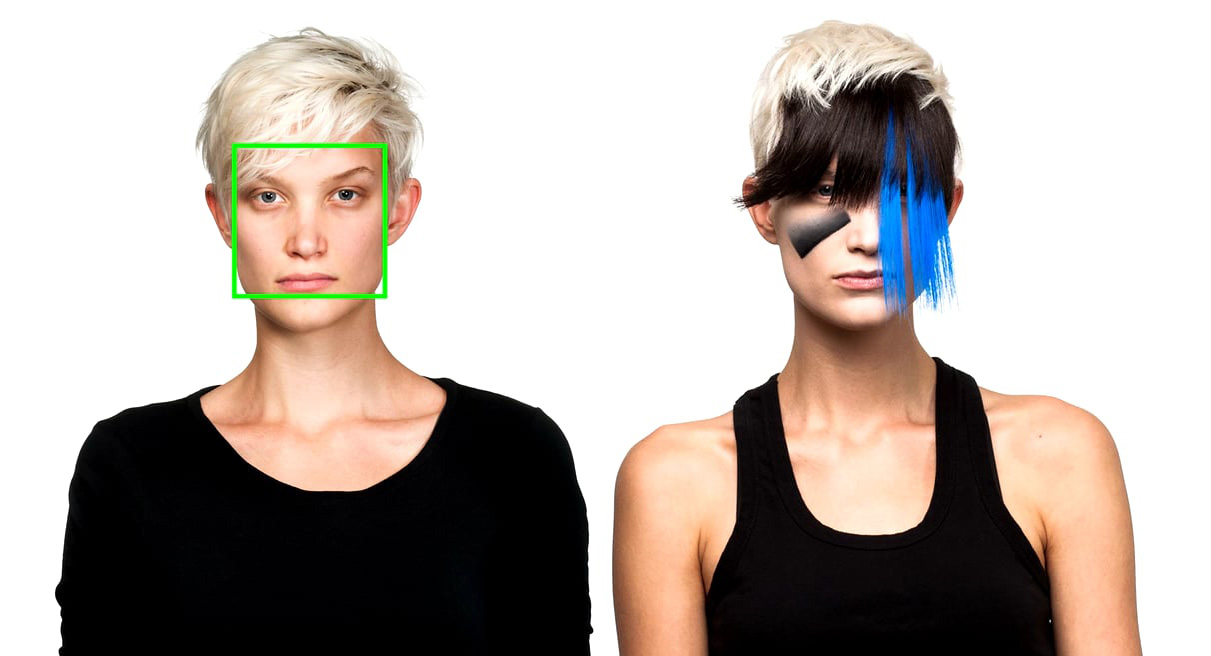

In 2010 artist and technologist Adam Harvey initiated a media art project called CV Dazzle.9 It is a set of fashion strategies for making your face unrecognizable by face recognition algorithms. These strategies have an exciting visual flair (including eccentric make-up and hairdos), showing again that a style driven by tactics can indeed be æsthetically significant.

If we apply the same logic to textual instead of visual media, we get a version of textual expression embedded as playful encryption. That is the core concept of the Tactical Emotions10 project: to reapproach Synesketch only to use it in a game of contemporary dazzle.

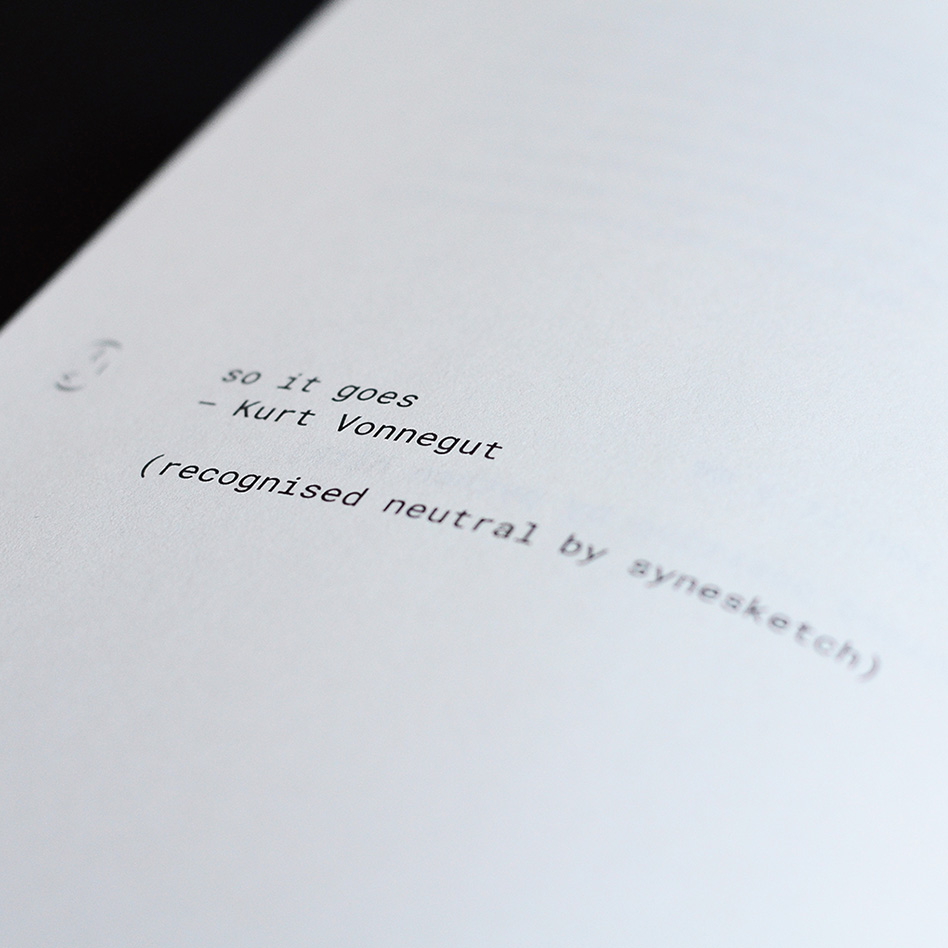

Similar to Dazzle battleships and their artistic camouflage, the intention behind Tactical Emotions is to deliberately confuse and fool textual emotion recognition systems and software tools for sentiment analysis. Not only Synesketch, but also Python NLTK11 (for English) and Inspiratron12 (for Serbo-Croatian). This is done by searching for phrases, sentences, styles, verses, and text fragments whose emotional meaning these systems couldn’t interpret – yet humans can. For example, if you type in “I am happy but”, Synesketch will recognize a positive emotion. We as humans, however, know this “but” changes everything. This offers a novel way of looking at literary æsthetics.

Take this sentence: “It is meaningless to love.” It would not be hard to agree that it is not a very positive proposition, however Python NLTK recognized it as such, probably because the affective weight of the word “love” (which is positive) outweights the word “meaningless” (which is negative). A line from Oskar Davičo's poem, “love is a beacon and saved sailors,” turns out negative. Is it because it alludes to a shipwreck? If John Lennon's “a working class hero is something to be” gets recognised as negative, does it mean that algorithms perceive “working class” itself as something negative? Banal statistical vulgarity of sentiment analysis algorithms, when read and experienced by humans, turns into fine poetic irony.

Metaphors and allegories have always been, at least in part, a form of strategic encryption of meaning. What makes it new is the computational aspect of contemporary surveillance, control, and machine-mediated power. Tactical Emotion is, thus, writing against the machine, recontextualized as poetry.

One could say that poetry – by this very definition – is something computers cannot recognize. Instead, poetry becomes digital camouflage. ↓

it is meaningless to love.

is something to be.

Just loved you.

between a colon

and a closed bracket,

and your textual symbol

your textual emoticon

such as this one : )

will not be turned

automatically

into an artificial emoji

such as this one 🙂

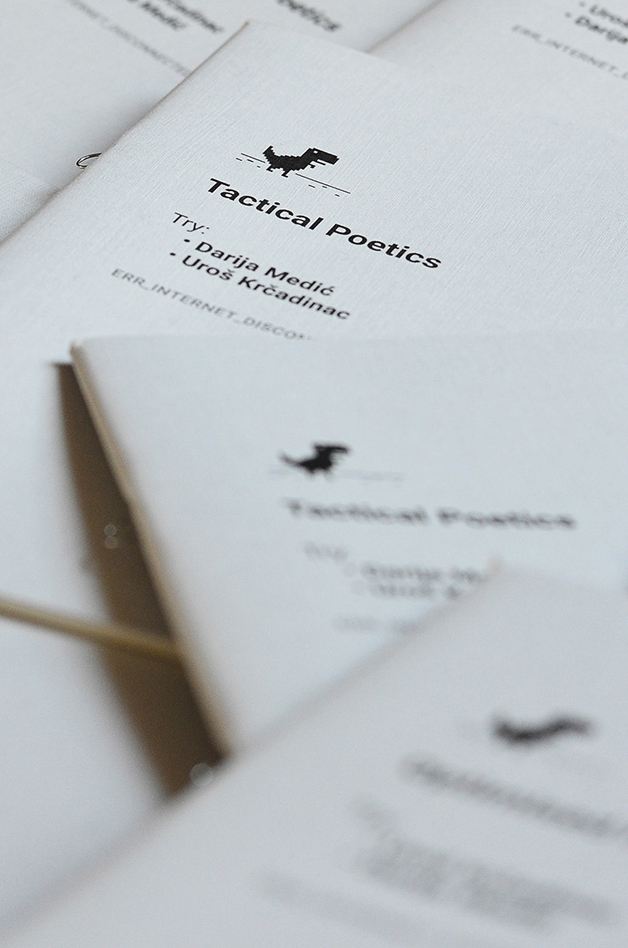

↑ The original concept for Tactical Poetics was conceived in 2018 for the Digital Poetry Workshop, organized as a part of the Art + Science conference in Belgrade. The concept was also presented at TEDxMokrin. Eventually, it grew into a collaboration with artist and researcher Darija Medić, with whom I've co-written a pair of books, Optimized Poetics & Tactical Poetics, published by the Multimedia Institute in 2020. ■