This is one of the philosophical dangers of using widespread automation, which is that it fixes meaning.

—

Optimized Emotions project starts with the question: how are words used today?1 Of course, we write novels and we curse, as humans have always done, we sing and we name things. Yet, drowned in endless digital streams, we feel something is different.

A friend of mine, a short-story writer from the US, told me that when she writes primarily for the Internet, she carefully chooses words for her stories in terms of Internet search terms associated with topics she writes about. For instance, if she writes about immigration issues, she looks for keywords Internet algorithms associate with these social topics. The goal is to get her story classified and positioned within the right thematic cluster, so it could be found more easily by possible readers who use Internet search engines, the primary one being Google. In other words, she is writing for both humans and algorithms. One could say she is doing search engine optimization (SEO)2 of her literary prose.

In his paper “Linguistic Capitalism and Algorithmic Mediation”3, prof. Frederic Kaplan explains the logic of word commodification and monetization: “Google is certainly the first economic actor to have understood that the logic of linguistic capitalism implies not an economy of attention but an economy of expression. The goal in this new economic game is not to catch the users’ gaze but to develop intimate and sustainable linguistic relationships with the largest possible number of users in order to model linguistic change accurately and mediate linguistic expression systematically.” In this econo-linguistic game, words are mere indices of goods and services. Economic indicators, markers, vectors, taxonomy mechanisms for machine classification. “Should we expect something like a pidgin or a creole to emerge,” Kaplan rightly wonders, “whose syntax and vocabulary would be influenced by the linguistic capacity of machines and economic value of words?”.

This new dialect, however, this techno-capitalist creole, might still not be completely devoid of poetic value. Pip Thornton4, a researcher and artist from Edinburgh, created a body of text-based work related to linguistic capitalism5. “While concentrating on exploiting language for money,” she says, “Google have in effect let money control the narrative.”6

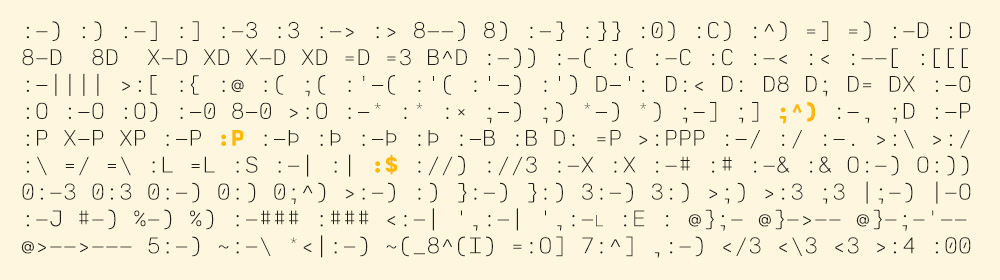

Similar to Thornton, Optimised Emotions utilise Google Ad Keyword Planner, an app that helps customers choose right keywords for their Google Ads. Among other things, the app names prices of keywords you decide to use in your ad. This is how the price for the ad is determined, via a bid system. Prices change all the time, yet not drastically. Words associated with lucrative industries are more expensive than others, as people google them more often. In addition, the app gives you additional keyword suggestions based on what these algorithms thinks you want to sell with the text you provided. Through these optimal suggestions, you can guess what does Google assume you are selling with your words – because of course you are selling something, that is what words are for, right?

Keyword Planner is meant to be used for marketing-driven text, yet no law exists that forbid you from putting any text as an input to its algorithm. This is how Optimized Emotions work: you put an old poem inside the Keyword Planner, and let the algorithm tell you its monetary value (if it were an ad) and how you could optimise your word choice (if you wish your ad to be more effective). The results are recontextualized as new poetry.

Let us think: how quiet are, the snowy

peaks of the Urals.

If we get sad over a pale figure,

whom we have lost on some evening,

we know that, somewhere, a rivulet,

instead of it, all in red, is flowing!

One love, morning in foreign land,

envelops our soul, gets tighter,

in endless peace of blue seas,

from which the crimson corals glitter,

like, from my distant homeland, cherries.

We wake up at night, smiling dearly,

to the Moon with its bow bent,

caressing the distant hills, tenderly,

and icy mountains, with our hand.

dried sour cherries

coral reef

all quiet on the western front

cherry tomatoes

peak meaning

maraschino cherries

quiet book

mount airy casino resort

homeland netflix

chocolate covered cherries

barbados cherry

sumatra indonesia

silent please

quiet the power of introverts

CTR 9.6%

Avg. CPC US$0.03

Avg. Position 1.4

18 Clicks

190 Impressions

now US$ 0.03

we US$ 0.05

are US$ 0.01

carefree US$ 0

tender US$ 0

and US$ 0.02

airy US$ 0

They walk the Earth and their eyes

large and mute grow near the things.

Leaning an ear

on silence that surrounds them and torments them,

poets are eternal blinking in the world.

richest people in the world

sad poetry

myopia

eye doctor near me

love poems

walt whitman

green eyes

google world

new year greeting cards in rhyme

book suggestions

simple quote greeting card

beautiful quotes

sad quotes

love dedication birthday

beautiful sentences

CTR 9.9%

Avg. CPC US$0.15

Avg. Position 1.4

58 Clicks

590 Impressions

For whom I would do anything

I wish I had

One little green tree

To run after me down the street

big little lies

pretty little liars

street view

google street view

bonsai

all of me

google maps street view

let me down slowly

take me to church

love me like you do

let me love you

baobab

call me

lemon tree

bonsai tree

acacia

quercus

mi amor

money tree

follow me

CTR 14.9%

Avg. CPC US$0.02

Avg. Position 2

4 Click

25 Impressions

I dream, mother. I dream, mother, that I am singing

and you are asking me, in my dream:

What are you doing, my dear son?

What are you singing of, my son, in your dream?

I am singing, mother, of a house

and now I don't have a house.

This is what I'm singing of, mother.

Of a voice I had, mother,

In a language I had, mother,

Yet now I don't have neither voice nor language.

With a voice I don't have

In a language I don't have

Of a house I don't have

I sing my song, mother.

multilingual

google translate photo

i can do bad all by myself

profanity meaning

how have you been

what do you want

metaphor

i am mother

mom and son

dream interpretation

working moms

figurative language

look what you made me do

dream moods

dialect

lucid dream

do you love me

how do you do

languages online

how to find percentage

i want to know what love is

CTR 5.3%

Avg. CPC US$0.57

Avg. Position 0.68

120 Clicks

2.2K Impressions

So, how does Google interpret local poetry?7 Or – what does Google think these poets advertize?

Results vary depending on language (original poems or translations) and target countries, but patterns do emerge. Mika Antić, for example, markets online dating, cosmetics, and astrology, Vasko Popa is more into carpentry and agriculture, Abdulah Sidran advertises language apps, Miloš Crnjanski and Ljubomir Micić work within the tourist industry, while Milena Marković belongs to the online pornographic and sex market. Among the selected bunch, Antun Branko Šimić is the only one whose poetry Google associates with anything remotely poetic, suggestions being, for instance, “love verses” and “sad quotes”. Who dares to say poetry does not have a utilitarian value? People need textual clichés for book dedications and wedding toasts.

Writing about rock and roll8, Dragan Ambrozić questioned the generations who want to be objects and are able to feel themselves only in clichés. In the culture of emojis and affective computing, generative texts and optimized content, that is the question for all of us: will we be objects or subjects of software? Will we develop a sensitivity towards algorithmic regimes? Will we be able to feel them and how will we respond to them creatively? Will we even be able to recognize our own emotions if they are not formulated as digital clichés?

Katherine Hayles said that “we become the codes we punch.”9 If we consider the transformative potential of the embodiment of everyday digital practices, we will realize that poetry is not just a form of expression. It becomes a form of survival. ■